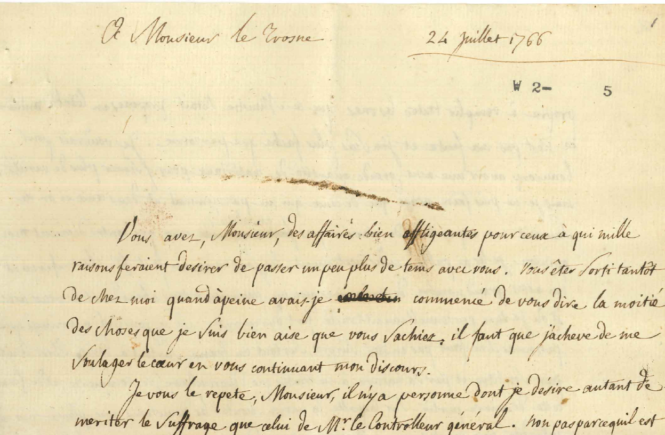

Letter from Dupont (de Nemours) to G.-F. Le Trosne

July 24th, 1766

translated by Benoît Malbranque

[Eleutherian Mills Historical Library, Winterthur Manuscripts, W2-5.]

To Mr. Le Trosne

24 July 1766

You have very distressing affairs, Sir, for those who would have a thousand reasons to wish to spend a little more time with you. You left my house when I had barely started to tell you half of the things that I had to say; I must finish relieving my heart by continuing my speech to you.

Let me repeat, Sir, that there is no one whom I desire to deserve the applause more than the Contrôleur général [1], and not because he is minister, wise men set apart the dignities, but because among all the ministers that we have had for a very long time, he is the only one who has carried out the most operations useful to the nation, because we owe him the freedom in the grain trade[2], because he has done all that depended on him to give us also that of the maritime trade[3]of this precious commodity, because he felt it was good to discourage the ruinous use of wealth in rents which only increase idleness and overload agriculture, because he had the courage to submit them to taxation, because he had a tariff drawn up for the reduction of weights and measures, because he undertook the inventory of the exploitation wealth and the net productof the kingdom (on which I worked, as you know[4], and I hope will continue to do so in the future), because he established the Journal de l’agriculture, du commerce et des finances[5], which is devoted to discussions that may some day make it a work of the greatest importance for the nation. [6]If this work is not yet perfectly suited to fulfil all the objectives that this minister had when he established it[7], it is not my fault and there is no one who is more sorry about it. I would very much like to have a large enough quantity of material to bring more variety, but I can only make use of the writings which are sent to me and among these one cannot reproach me for not having published those which promoted contrary opinion: I published those indiscriminately, the journal is proof of it, containing a fairly large number of writings which seem very absurd to me and to you too, and in which I am personally treated very harshly. If this newspaper annoyed a few people, it should not come as a surprise especially in France, especially in Paris. It is limited by his title and by its very nature to those three topics which are agriculture, commerce, and finance; and this last part, about which the public was eager to read[8], the company, through twenty reiterated recommendations, prevented me from covering it. The two other topics remain, whose practice is tedious, especially as they are almost always completely ignored by the small number of those who get involved in writing (those who are skilful in the practice are operating as a business and do not write), and whose theory is abstract, especially since it forms a new science to which attention has only been given for a short number of years. [9]I made the most of the state of shortage I was left with in terms of material; the newspaper dealt with very important questions, very interesting for the public good, such as the competition of freight for the export of grain[10], the interest of money, the prohibitive laws on the colonial trade, the means of remedying the depopulation of horses, and the question whether trade and industry should be left to operate freely, without being subjected to any taxation, or whether they should rather be regulated, even prohibited in some parts, and in general be subjected to taxation (a question in which I admit that I stand with the advocates of the first thesis), and we see the birth in the issue of July of the question of the current state of the population of the kingdom, and that of the freedom of grain maritime trade, in the dealing of which, incidentally, I only commented on the principles contained in an excellent letter that the Contrôleur général wrote on this subject to the duke of Choiseul, in the company of which I had the pleasure of reading it. No doubt I would have added even more variety in the journal if only I had been given the proper material; but since Mr. Cromot and Mr. Mesnard relied on Mr. Henique, their partner, to direct our work, the journal was left to my own resources and that of my friends, and my work was hampered. When dealing with the great questions I have just mentioned, I inserted as much notes and observations as I could, on the balance of trade, on active and passive commerce, on exclusive privileges, on trade wars, on the English loans, on the causes which make our navigation more expensive than that of foreigners and which should be remedied, on the advantages of the constitution of the government of France, and on the disadvantages of that of England, on the physical causes which determine the position of manufactures, on mines, etc., etc. Yet I have been formally and expressly forbidden to make any more notes, and it has forced me to write articles which are printed in a bigger character size than the notes, and thus fill up more space and leave less room for variety. That is not all: you know Mr. Henique’s prevention for my colleague; to have placed me under Mr. Henique meant my colleague would be acting like a despot towards me. You know that unfortunately and to the shame of most men of letters, these men are subject to the nasty little disease that is called professional jealousy; my colleague was suffering from it immensely, in his relation with me; he saw with great pain that the kind of work I was undertaking occasionally attracted me compliments and put me in connection with several respectable and established men. [11]He believed that in order to achieve the same result for himself, he had to distort the Gazette for which he is responsible and which was established as a purely historical and descriptive work, and to insert in it a collection of dissertations and polemics, just like the Journal. Mr. Henique gave him his support and assisted him in this singular project. They consequently intercepted and allocated to the Gazette all the materials which were not made for it, and which would have been of great value for the Journal; they placed there, and cut into a hundred pieces by the tiresome phrase To be continued in the next issue, the whole discussion for and against the usefulness of the regulations on manufactures, an interesting matter which belongs to the journal by its very nature, and which the Contrôleur général clearly intended to fill the Journal, when he sent me the first piece of writing we received on this subject, with the positive order to use itin the journal. They also inserted in the Gazette the long project of Mr. Delaborde for the establishment of the culture of flax in Armagnac and rebuttals of this project. They have included a large letter by an inhabitant of Saint-Domingue in response to a previous one written by merchants of Saint-Malo, dealing with the colonies, which is yet another subject perfectly suitable for the journal, so much so that we have been covering it for six months. I would never finish if I ventured to mention all the writings that they took from me (something which was easy for them to do, since all the materials are sent to my colleague) and which would have allowed me to better satisfy the public and to better meet the expectations of the minister, so wisely and so nobly set out in the draft essay which was published at the beginning of the issue of March, and which he was too modest to sign with his name. In order to find space in the gazette to satisfy this fury to discuss which became dominant in my colleague and consequently in Mr. Henique, they removed the listing of the prices of grains, hemp, flax, wools, silks, wines, oils, irons; all these informations, so greatly interesting for agriculture, for domestic as well as foreign trade, and even for the public treasury, whose management is depending on the price of commodities.

However, they should have been all the more restrained in making suppressions that the Contrôleur général, who being a great minister had grasped the importance of this series of prices, had kindly written more than sixty letters to the provincial intendants, in order to obtain them for us. Three months ago they suppressed an invention that was very fortunate for the eradication of wolves, and whose publication was all the more urgent because as this matter requires an order from the king, the administration must be given enough time to ponder over it long before the time of implementation. They cut into pieces and mutilated without consulting me almost every single piece of writing that I gave for the Gazette and in particular most of the newspaper notices that were supposed to be published in order to engage subscribers who only have the Gazette without the Journal to subscribe also to the latter, but all those writings have been disfigured to the point of enabling them to produce the very opposite effect. My formal reprimands regarding the materials that were taken from me, the suppressions that were being made, and the absolute failure to abide by the general spirit of the institution of both the Gazette and the Journal, were treated by Mr. Henique and by my colleague as childish and the only effect it had was to cause me distressing annoyances. I do not know whether those actions were dictated by the prospect of obtaining success for both parts of our periodical work, but I believe quite on the contrary, that nothing is more likely to ruin them both. I can assure you that if it had not been for the deference which I owe to the intentions of the Contrôleur général, who entrusted me with this work, and the personal attachment that I have to Mr. Mesnard and Mr. Cromot, I would have already stepped down twenty times. Mr. Henique and my colleague have managed to make my life and my work so unpleasant, that if this continues I will regard as a favor from the minister and as a mark of benevolence on the part of Mr. Cromot and Mr. Mesnard, the permission to leave the journal and to go back to the inventory work of generalities and the study of expenses and the products of the culture, that once was my occupation. One can have a much better time negotiating, studying, working, living amond farmers, good and honest peasants, than with jealous and allegedly literary colleagues. I look forward to meeting Mr. Cromot and Mr. Mesnard and telling them about my feelings regarding this matter. I feel sorry that they chose someone other than themselves to run their business.

Yet I realize, my dear friend, that I never seem to finish and that I am trespassing on your patience. Farewell then, please forgive me and love me, you know that the unfortunate are talkative, but they are deeply attached to the people they love; and you have still a thousand other reasons to count on the attachment with which I will always be

Yours truly,

Dupont

Sir and dear friend, I still have a word to say to you, it is on the subject of your criticism, that I have overly praised the author of the economic table. Had this author been an established man, had he enjoyed the kind of reputation that I once saw him having, I would have been careful not to overly praise him, lest I be suspected of considering my own interests. But since he has no official occupation nor credit, I believed that I could and should pay tribute to his merit alone. If my belief was not found to be proper, it would be proof of what I said, that posterity alone would do him justice. Besides, it was my fate to be scolded for this praise because I was strongly admonished by the old Quesnay himself.

————————

[1]Since the end of 1763, L’Averdy was in charge of finances and held the title of Contrôleur général des finances(Comptroller-General of Finances).

[2]In July 1764, an edict established the free trade of grains.

[3]Cabotage, a notion covering trade by both national and foreign ships.

[4]Dupont was in charge of this in Soissons, where the intendant[public official in charge of a district] Méliand employed him in 1764.

[5]This journal was created en 1765, in addition to the existing Gazette du commerce, in order to ease the publication of theorical debates on some of the major issues of political economy.

[6]Adam Smith had 10 volumes of this journal in its library, covering the years 1765 to 1767. (J. Bonar, A Catalogue of the library of Adam Smith, 1894, p. 2.)

[7]L’Averdy intended to encourage economic debate with the aim of demonstrating to the general public the rationale behind his liberty-oriented reforms.

[8]The recent success of the Richesse de l’État(1763), a short book by Roussel de la Tour, and the wide debate it created, is evidence enough of this eagerness.

[9]Although they recognized Boisguilbert as a forerunner, the physiocrats did not go back futher than Quesnay and Mirabeau, that is, eight or ten years earlier, to date the proper origin of the economic science.

[10]Le Trosne had written extensively on this issue in the Gazette du commerceand later in the Journal de l’agriculture, du commerce et des finances.