1768 — THE INTERNAL DISPUTES

WITHIN THE SO-CALLED SCHOOL

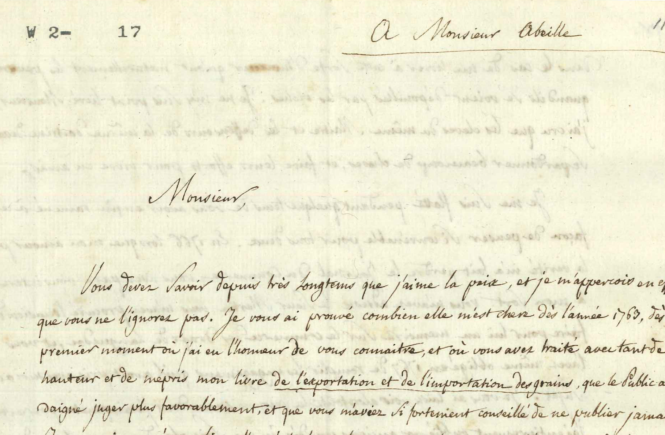

Letter from Dupont (de Nemours) to L.-P. Abeille

Undated [circa the end of 1768] — Translated by Benoît Malbranque

[Eleutherian Mills Historical Library, Winterthur Manuscripts, W2-17.]

To Mr. Abeille

Sir,

You must have known for a very long time just how much I love peace, and your letter confirms me that you are indeed well aware of it. I have proved you how much peace is dear to me as soon as 1763, that is, from the first moment we met, and at a time when you looked so negatively on my book De l’exportation et de l’importation des grains[1], which was nonetheless very well received in the public, and which you strongly advised me never to publish. I have proved you how much peace is dear to me when you forbade me, back in 1764, from finishing a treatise on luxury and then one on trade, that were both under way; and when you forbade me from doing so for no valid reason, since you did not publish them yourself, and disdained the use of the exclusive privilege that you were eager to secure on this matter. I proved to you how dear it is to me when, despite the instructions of Mr. Quesnay, you snatched from me the notes he had made on Mr. Mably’s treaty on public law[2], and when you consistently refused to return, neither to Mr. Quesnay nor to me, these notes that this respectable man had made only for me, for my instruction, for my personal use, and as a way to help and guide me in a work I was then in charge of, as I could prove you with the very letters sent to me by Mr. Quesnay. Five years ago, I was only 23 years old, I was perfectly unknown, and in all respects I was in great need of education and help; you, on the other hand, were more than a man, your reputation was already high, you no longer needed to be led and supported; and therefore I was experiencing the kind of torment that the poor so naturally suffer when being robbed by the rich. I did not react to it, Sir, for I believed that scholars working under the same teacher and promoting the same doctrine should forgive each other many things, and do their utmost to live as friends.

I flattered myself for a while that I had finally brought you over to this way of thinking that I believed to be so suitable for both of us. In 1766, when my love for truth caused me to lose the Journal du Commerce[3], you seemed to show interest in me. You sent me to Mr. Martin, you gave me the opportunity to write for him an essay on the Languedoc linen trade, and you even reminded him in 1767 to fulfill the commitments he had made with me about it. I then showed you how grateful I was for this service; I strived to forget your old ways, and gave in to the pleasure of believing that you would never try to remind me of them.

Before and since that time I have missed no opportunity to show consideration, deference, and respect towards you; to praise your writings, your knowledge and your talents. Therefore, I do not understand why you choose to persecute me now.

Will you never be able to allow me to complete peacefully a book which you have been informed I have started? Why does it matter to you that I write or do not write an abridged history of the good economic writings published in France? [4]If this historic overview is poorly executed, I will be the only one to blame; and you will always be at liberty to criticize me. Do you think that I am insensitive enough not to feel how insulting your redoubled pleas are, demanding me to mention neither you nor your writings?

You say you have good reasons for not telling me the circumstances that lead you to insult me in such a way. The very fact that you are not willing to express these reasons, make them all the more easy to guess. At least it is quite clear to me that you are looking for an opportunity to complain about me. This one is indeed very suitable, because if I refuse what you ask of me, you will complain about my unwillingness, when faced with your pleas; and if I keep the silence you demand, your friends will complain, they will accuse me of injustice and partiality against you, and they will universally decry my work with seemingly good reasons.

You emphasize greatly the kind of service that you are rendering me by signing your letter, and you explain me how I could very well show it to those who would reproach me; but it is not from those who know us both that I fear reproach, and I will not take your letter to Brittany[5]and present it to the many people who are strangers to me.

The most reasonable and fairest path in all respects would be to confine myself to the plan I proposed to you in my previous letter, that is, to keep your name silent and to speak only of your writings, for it is my right, along with all the others writings that I can find deserving. You chose to refuse this way out, Sir; and you say you will complain loudly about me if I follow it; I surrender to you once again for the sake of peace. But please remember, Sir, that I do not want any reproach for having done what you wanted, and if it occurs to me that someone of your friends complains about my behavior with you I have my justification in hand and I shall publish our correspondence on this subject.

Before ending this letter, I must tell you what I have done to comply with your views, which I cannot endorse. I delayed the publication of my volume, which had been ready for three days. I had two sheets reprinted. I have not deleted from the notice the mention of the publications of the society of Brittany[6]because whatever share you had in these publications, they cannot be considered as your work, they are the work of the Society of Brittany which did not not forbidden me to make use of it and which incidentally would never have forbidden me, because companies are usually more civil than individuals, and also because companies of citizens never treat with disdain other citizens who zealously apply themselves to the study of the public good. But when reviewing the first of the works which are properly yours, I set the tone that you asked of me and I remained silent about your other works. That said, I cannot expect that you will be content, Sir; I see too clearly that I must give up any hope of satisfying you. But it is enough for me to have put justice on my side and to have proved once again that I would very much like to avoid the divisions that are so harmful to sciences, so ridiculous in themselves and so costly for scholars; those divisions that you want to create and that I would rather like to hide away when you put them forward.

Believe me, Sir, yours truly, etc.

———————–

[1]The first book published by Dupont (in 1764), and one which was indeed quite successful.

[2]Le droit public de l’Europe, fondé sur les traités (1748), by Gabriel Bonnot de Mably (1709-1785).

[3]The Journal de l’agriculture, du commerce et des finances.

[4]Dupont is referring to his « Notice abrégée des différents écrits modernes qui ont concouru en France à former la science de l’économie politique », published in 1769 in the Éphémérides du Citoyen. It is incidentally the first history of economic thought ever written.

[5]Louis-Paul Abeille, born in Toulouse, moved to Brittany as a young man and was working in the Parlement de Bretagne, in Rennes.

[6]The two volumes of Corps d’observations de la Société royale d’agriculture, de commerce et des arts de Bretagne, published in 1760 and 1762.