1885 — THE PRECISE MEANING AND SCOPE

OF MOLINARI’S ANARCHO-CAPITALISM

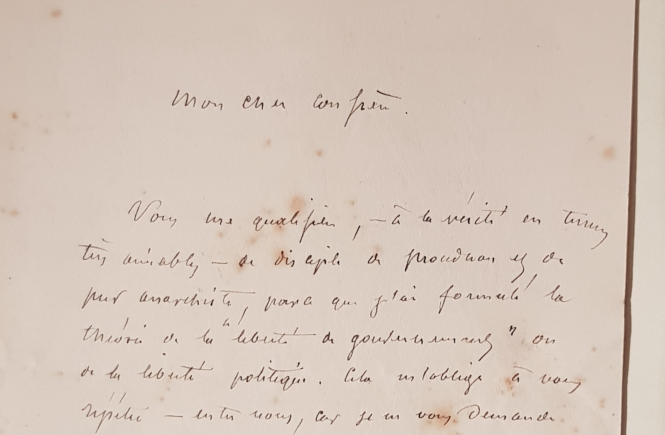

Letter from Gustave de Molinari to Arthur Mangin

8 November 1885

Translated by Benoît Malbranque

[Private collection.]

Paris, 8 November 1885

My dear fellow economist,

You characterize me—in the most friendly way possible—as a follower of Proudhon and as a pure anarchist, because I have developed the theory of “freedom of government” or political freedom. This causes me to reiterate before you—and you only, for I am not asking you to publish my letter [1] —that this theory has nothing in common with that of anarchy or anarchy, namely the absence of government. I thought I made myself clear in my last two large volumes [2] about what had been the justification of government monopoly and political servitude, why this justification had gradually ceased to exist, and how freedom of government had become possible. If a mind as sharp as yours has failed to grasp my argument, I must not have laid it out with enough clarity. I am therefore bound to write a third volume in order to make the first two intelligible.

For the moment, I shall restrict myself to underlining that freedom of government or political freedom is only an application of the general principle of freedom, and that it does not more imply the suppression of government than did the abolition of the salt tax, for example, and its replacement by free production and optional compensation for salt, imply the elimination of salt and salting.

In short, it is a radical liberal, if you want, and not an anarchist, who shakes your hand.

G. de Molinari.

[ANNEX. CHARLES BENOIST’S RECOLLECTIONS.] … In addition to the office of the Revue Bleue, I regularly visited that of the Journal des Économistes, which was adjacent to Guillaumin’s publishingcompany, located on rue de Richelieu. Every Saturday, in the late afternoon, the editor-in-chief, Gustave de Molinari, was receiving people. I cannot remember anyone whose conversation struck me more or as much as his. When discussing any issue, he had his own ideas and phrases. One could never be sure of what he was going to say, or how he was going to say it, except that he would say it like no one else. His originality went as far as paradox, and he carried paradox into theory. The economist who had characterized the State as a “necessary evil” was still a heretic to him. According to him, the State was undeniably evil, but not a necessary evil. In almost all cases, if not in absolutely all of them (and I cannot see one which he found to be an exception), he was willing to do without the State. Why not form private companies that would distribute order, secu-rity, namely government, like those which distribute water, gas or electricity? Everyone would subscribe to the one company that he pleases. Religion itself would be put into shares and provided at the best possible price by free competition. André Liesse [3], Joseph Chailley [4] and I listened to him in awe; but, on leaving, in spite of the ardor of our faith as neophytes, we agreed among ourselves that perhaps the prophet was going too far. Yet he was so funny, in a field where it is difficult, and so rare, to be! What would he have not made interesting and exciting, and what could have seemed boring when discussed by him? … (Charles Benoist, « Mes débuts littéraires », Revue bleue, politique et littéraire, 1932, p. 329.)

[1] Arthur Mangin was writing for Paul Leroy-Beaulieu’s Économiste français.

[2] L’évolution économique du dix-neuvième siècle. Théorie du progrès (1880) and L’évolution politique et la Révolution (1885).

[4] Joseph Chailley (1854-1928), who changed his name to Chailley-Bert after marrying Henriette Bert, daughter of Paul Bert (1833-1886), member of Parliament, minister and later resident general of the French Republic in Annam and Tonkin.